Global equities last week fell a modest 0.6% or so in both sterling and local currency terms. This still left markets up a healthy 2.3% and 3.7% respectively over May as a whole and around their end-March highs on both measures.

The US and UK were both down around 0.5% while Japan, which has been performing poorly recently hit by the persistent weakness of the yen, was the only market to post a gain.

The US was as usual the main centre of attention on the macro side with the Fed’s favourite inflation measure up for release. This came in broadly in line with expectations with core inflation unchanged at 2.8%. Even this, however, was greeted with relief by markets which feared another set of poor inflation numbers might kybosh the prospect for rate cuts later this year.

Meanwhile, US growth in the first quarter was revised down to a sluggish annualised 1.3% and consumer spending is off to a weak start this quarter. Even so, the slowdown in the economy still seems limited with growth on track to return to a more respectable 2.5% or so in the second quarter.

Bonds as ever remain crucial to the outlook for equities, particularly with government bond yields pushing higher again in recent months. Prospective interest rate movements are usually the main driver here but budget deficits – as Lizz Truss found out to her cost – can far from be ignored.

Last week’s auctions of US government debt saw lacklustre demand, putting yields under upward pressure as worries surfaced over the large budget deficit which totalled as much as 6.3% of GDP last year (versus 4.4% in the UK). However, Friday’s inflation numbers then came to the rescue and yields ended the week little changed.

The sharp rise in yields over the last couple of years means the gap between government bond yields and the dividend yield paid by global equities is at its largest since before the global financial crisis. This has left equity valuations looking rather stretched and means further market gains will need to be driven by corporate earnings rather than a valuation re-rating.

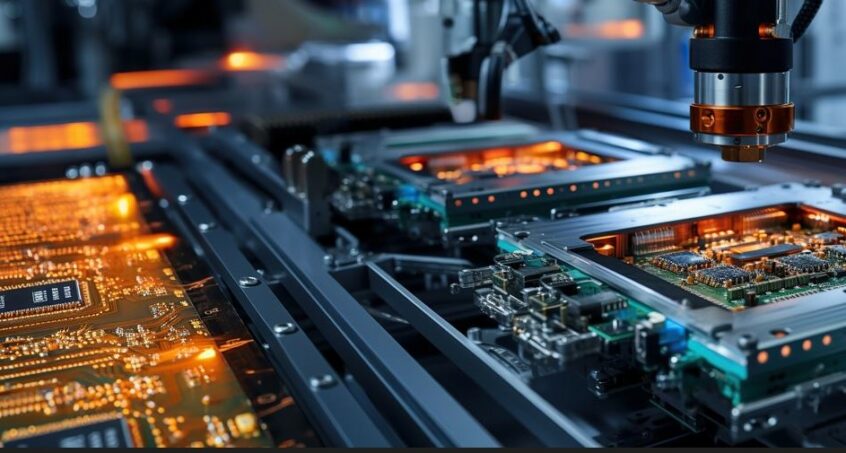

Fortunately, earnings are well placed to grow further over the coming year on the back of the resilience of the global economy and the strong performance of the majority of the Magnificent Seven tech stocks. Indeed Nvidia, the chip manufacturer and golden child of the moment, announced at the weekend sooner than expected the next generation of AI processing chips, suggesting its golden run may well continue a little longer.

Back here in the UK, the Conservatives and Labour are doing their very best to convince us that neither will raise taxes if they win the election. Having already ruled out hikes in national insurance and income tax, VAT is also now ruled out by both parties – with the exception of Labour’s plan to impose VAT on private school fees.

The problem is that, whoever wins the election, these promises will be hard to keep. Both parties are signed up to the fiscal rule requiring that government debt should be falling as a share of output in five years’ time. But this is only attainable with no tax rises if they stick to the current public spending plans which pencil in implausibly low growth of 1% p.a in real terms.

The fiscal bind means both parties will be severely constrained in their room for manoeuvre and as a result the election is not really a big deal for the markets. Much more important is the nascent recovery in the economy and the prospect of interest rates starting to be cut over the summer – and the latter lies in the hands of the BOE not the government.

This week, the European Central Bank meeting on Thursday will be the highlight. Despite last week’s news that core inflation in the Eurozone unexpectedly rose from 2.7% to 2.9% in May, the ECB still looks very likely to kick off the rate cutting cycle with a 0.25% reduction to 3.75%. But as ever, the US employment numbers on Friday will also be a major focus.

Rupert Thompson – Chief Economist