If you listened to nothing but the rhetoric, you would think economic policy will be very different going forward under a Labour or Conservative government. In fact, it very likely won’t.

Both parties are currently signed up to fiscal rules which severely constrain their room for manoeuvre, particularly the requirement that government debt be falling as a share of GDP in five years’ time. Less of a problem is the need also for government borrowing to be no more than 3% of GDP.

As a result of these constraints, while the parties differ in their spending and tax intentions – taxes and spending are together forecast to be some £20-25bn higher under Labour than Conservatives by the end of the next Parliament – the budget deficit forecasts are fairly similar for both parties.

Conservative manifesto policies are forecast to reduce tax receipts by £11bn or so per annum in five years’ time and are financed by spending cuts of a similar amount. More specifically, the plans are to cut the National Insurance rate by 2p and abolish it for the self-employed, raise the personal income tax threshold for pensioners and abolish stamp duty for first time buyers up to £425k. These cuts would be financed by cuts in welfare spending and reducing tax avoidance.

As for Labour, it plans to increase spending by around £9.5bn per annum by 2029 with half of the increase coming from its Green Prosperity Plan and the rest from increased spending on public services. £5bn or so would be funded by reducing tax avoidance (easier said than done) and taxing non-domiciled residents, £1.5bn from imposing VAT and business rates on private schools, £1.2bn from extending the windfall tax on oil and gas companies, and £0.6bn from raising the tax rate on private equity ‘carried interest’.

All the numbers above are actually quite small beer. Increased spending of £9.5bn, for example, amounts to all of 0.3% of GDP. So, the big question is what is the risk of a much larger increase in taxes and spending under Labour.

Taxes are already set to hit a new post-war high as a share of GDP over the next Parliament, largely due to the continuation of the freezing of personal income tax allowances. And Labour have joined the Conservatives in ruling out rises in income tax, national insurance, VAT and corporation tax which together account for three-quarters of total tax revenue.

Even so, there will be undoubted pressure to raise taxes yet further given the squeeze on government spending and dire state of many public services. Labour has also not ruled out raising capital gains tax or changing pension taxation.

There is also a good chance that the fiscal rules will be tweaked, as they have been on numerous occasions in the past, to give the government more leeway. Still, one factor certain to limit the appetite of Labour for large tax and spending increases will be the desire to avoid a Liz Truss ‘moment’. Indeed, Rachel Reeves has made a big song-and-dance about the need for stability.

As for other areas of divergence between the two parties, they are no longer that large. The relationship with Europe may become rather warmer under Labour but no major change is on the cards. No-one (including the Europeans) wants to re-open the Brexit can of worms and Reeves has ruled out rejoining the single market or customs union. Labour has also watered down its support for worker rights, so this shouldn’t pose a significant drag on company profitability.

All the above suggests the impact on the markets of a Labour victory is likely to be minimal. Even if it won a stonking majority, any wobble would very likely be short-lived. Foreign investors who own 60% of the market are unlikely to be scared off, not least because the Conservatives these days are hardly seen as a beacon of either economic competence or stability. If CGT rates were raised, this would be unlikely to pose much of a problem as foreign investors would be unaffected.

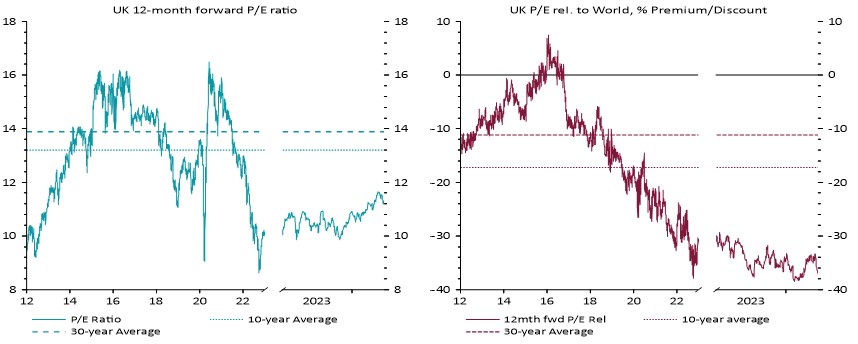

We believe UK equities are well placed to outperform from here regardless of the election result. The market is considerably cheaper than normal, both in absolute terms and relative to the rest of the world, and looks good value. Importantly, the UK economy is also now growing again, interest rates should start to be cut later this summer and M&A activity is picking up, helping this latent value to be realised.

If by any chance, you’re still skeptical that as an investor you’re basically better off ignoring the election, here are two final facts: first, 80% of FTSE 100 revenues come from overseas, so UK large cap stocks (unlike small cap) are not at the end of the day that exposed to domestic UK developments.

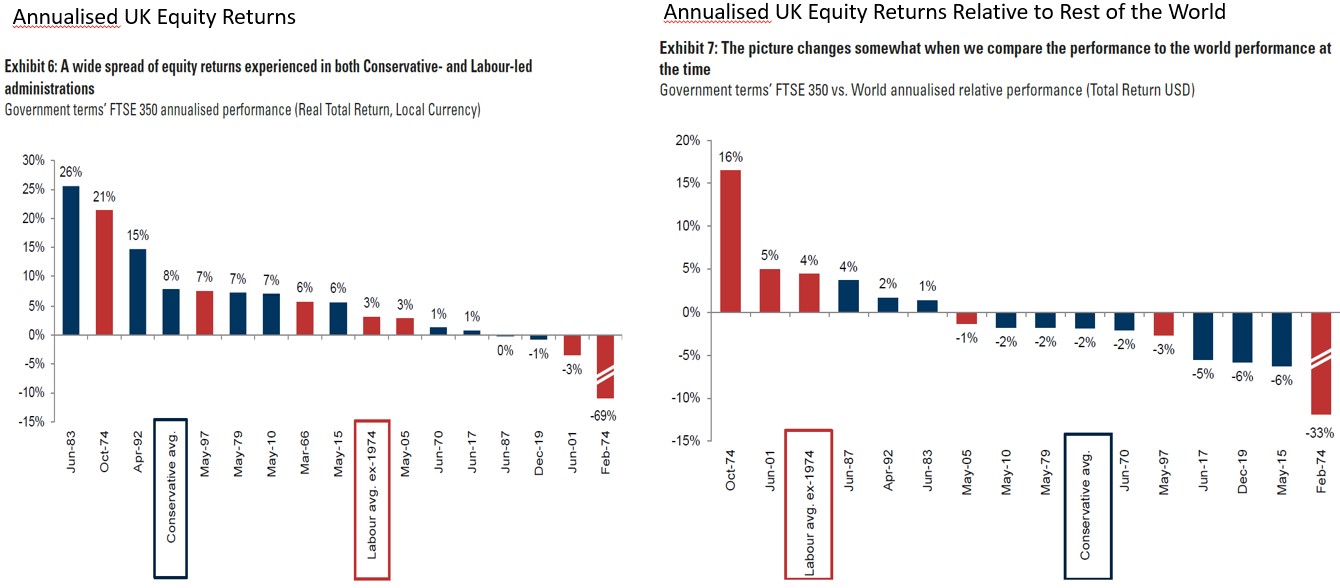

Second, history provides no clear message as to whether UK equities do better under Labour or Conservatives. Returns have varied widely. Whilst the average return has been better under Conservatives, if you isolate the UK effect by looking at the performance relative to other markets, you have on average seen better returns under Labour.

No Clear Difference in Performance of UK Equities Under Labour & Conservatives

Source: Goldman Sachs

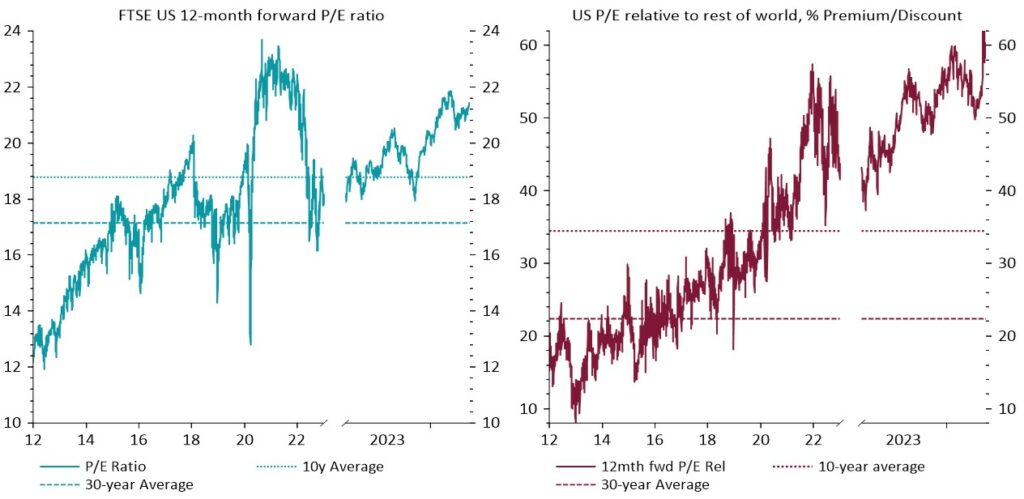

UK equities are very cheap

Source: Refinitiv

The French Election

Before we move onto discussing the US elections, the forthcoming French election merits a few words. Following the poor showing of his party in the recent European parliamentary elections (which saw a shift to the right but the centre-right parties still remaining the largest grouping) President Macron called a snap parliamentary election in France.

It is a two-stage process with the first vote on 30 June and a run-off on 7 July. The outcome is far from clear and Marine Le Pen’s far right party, or possibly even the left coalition, could well end up leading either a majority or minority government. As with most populist parties, the policies of the far-right and left parties if they gained power may well be rather more moderate than their pre-election rhetoric. Certainly, this has been the case in Italy since the right wing anti-European Georgia Meloni became Prime Minister two years ago.

The policy proposals of the far-right are still vague but include income tax cuts, higher public spending and reversal of the recent pension reform. As for the left, their proposals also include these elements as well as increased taxes on the wealthy. Both prospects basically threaten a large rise in the budget deficit which is already on the high side.

A government led by either would herald an era of uncertainty, a higher budget deficit and more anti-European stance and French markets have duly sold off on this prospect. French equities are down 5% or so since the election was called and bond yields have also risen.

We see the risk of this turning into a more systemic crisis for the Eurozone as very low. Still, this is undoubtedly an unwelcome development for the Eurozone, where the outlook had begun to look rather more positive, and may well remain a significant source of uncertainty and drag on European markets for some time to come.

The US Elections

While the UK and French elections will be a centre of attention only for the next few weeks, the US Presidential and Congressional elections on 5 November will be a major focus for markets for months to come.

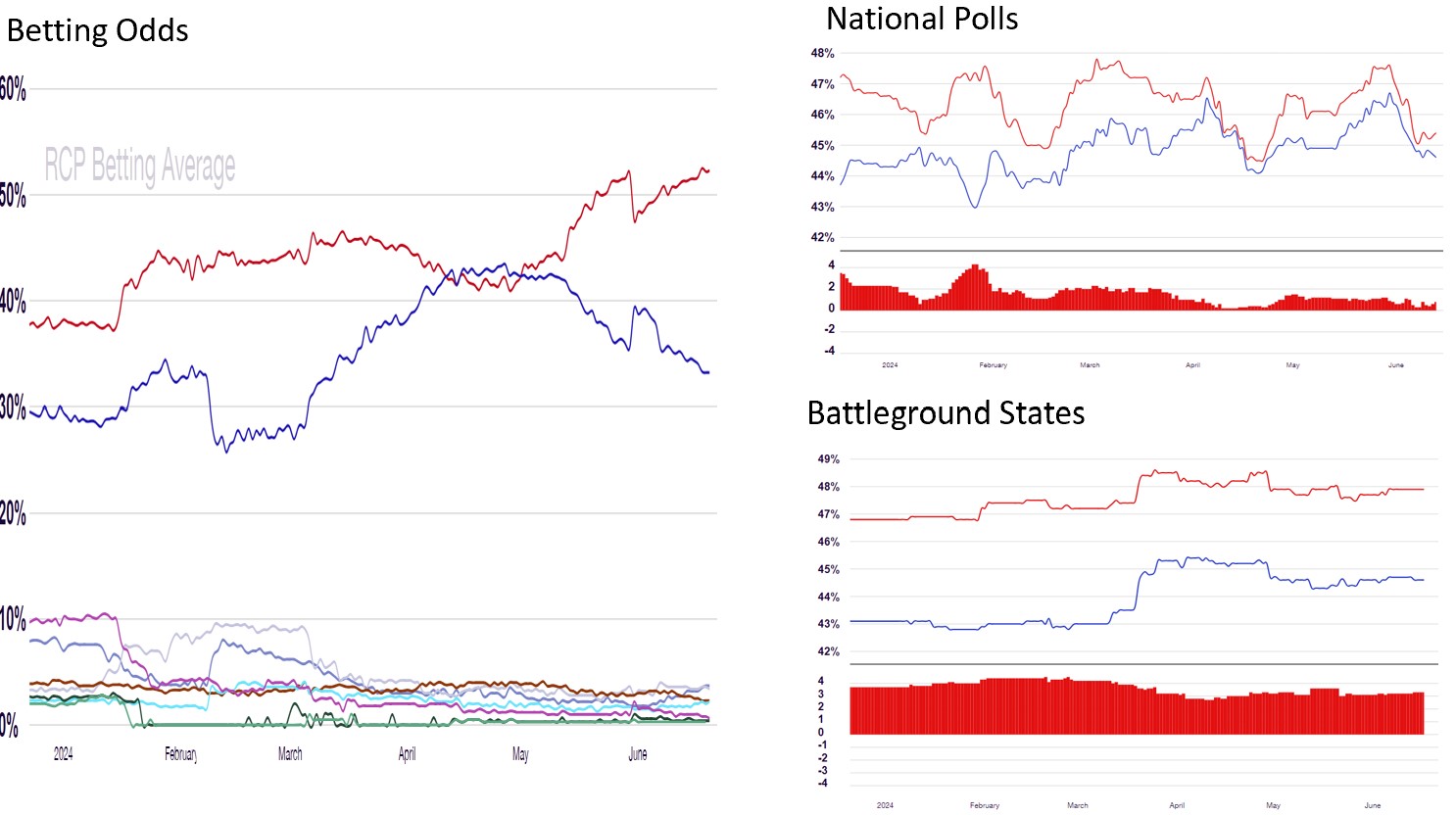

It is still quite early days but Trump is currently favourite to win the Presidency. Betting odds put his chances at 52% vs 33% for Biden. He is also ahead both in the national polls and crucially the key battleground states which will very likely decide the election.

As for Congress, one third of the 100 seats in the Senate are up for re-election. Currently, the Senate consists of 48 Democrats, 49 Republicans and 3 Independents who typically vote with the Democrats. The Republicans look quite likely to gain control, particularly if they win the White House as the Vice-President has a tie-breaking vote. All 435 seats of the House of Representatives are up for re-election, and it is a close call. Currently there are 221 Republicans and 213 Democrats.

Currently, the betting markets place the odds at 42% on a Republican Sweep and 15% on a Republican Presidential win but divided government. The corresponding odds for the Democrats are 22% for a Sweep and 22% for a divided government.

Presidential election: Betting Odds and Polls since the start of the year: Trump – Red; Biden – Blue

Source: Real Clear Politics

There are few lessons to be learnt from history as to whether equities do better under Democrats or Republicans. Markets have rather surprisingly on average done better under the Democrats. But this more reflects the economic backdrop prevailing at the time than the political colour of the administration. As for market performance during an election year, there is typically a bit more volatility ahead of the election with returns slightly higher afterwards as the uncertainty fades.

The market response to Trump’s victory in 2016 highlights the difficulty of trying to position an investment portfolio to benefit from a particular election result. Ahead of the election, markets rallied whenever Clinton’s prospects improved. But in the event, Trump’s unexpected victory caused only a very short-lived sell-off which was followed by a prolonged rally on hopes of tax cuts.

So, how different will economic policy be under a Trump or Biden administration? It depends in part on whether the President wins control of Congress. The ability of the President to push through changes in fiscal policy is severely constrained if there is a divided government.

Whatever the result, the new Administration looks set to spend much of next year fighting over how much of the personal tax cuts, which were introduced by Trump in 2017 and expire in 2025, will be extended. Rather more are likely to be extended under Trump, with the focus under Biden more on increasing government spending. Still, the large budget deficit, which amounted to 6.3% of GDP last year, will limit the ability of either President to implement major deficit-boosting measures.

That said, sharp rises in tariffs, which raise revenue, have been talked about by Trump and would increase the room for manoeuvre. And the President has considerable power in this area independent of Congress. Trump has talked of a 10% across-the-board-tariff which might raise at least $200bn (0.7% of GDP) and a 60% tariff increase on imports from China.

But Biden has also raised tariffs recently and, although tariff increases are likely to be larger under Trump, the direction of travel looks set to be the same. Indeed, the strategic hostility of the US to China is certain to continue whoever is elected.

The tariff increases would also be likely to raise inflation and depress growth because much of the additional costs would likely be passed onto consumers and it would take time for domestic producers to boost domestic production to make up for the reduced imports. Tariff increases of the size mooted by Trump would undoubtedly raise the possibility of retaliation and a trade war.

Finally, Trump has said he will not reappoint Powell as Fed Chair when his current term ends in 2026, increasing the uncertainties surrounding monetary policy down the road. But again, back in 2017, Trump in the event shied away from appointing a more radical candidate in favour of the more conventional Powell.

Where does this all leave us? As with the UK, with no intention of tweaking our investment positioning to benefit from a particular election outcome. Rather than the risk of a Trump victory, our view that US equities should underperform from here is driven primarily by their excessively high valuation. The increasingly large stock-specific risk, associated with Nvidia, Microsoft and Apple now accounting for as much as 20% of the main US equity index, also argues for having a sizeable portion of one’s equity exposure outside the US.

US equities are expensive

Source: Refinitiv

Rupert Thompson – Chief Economist